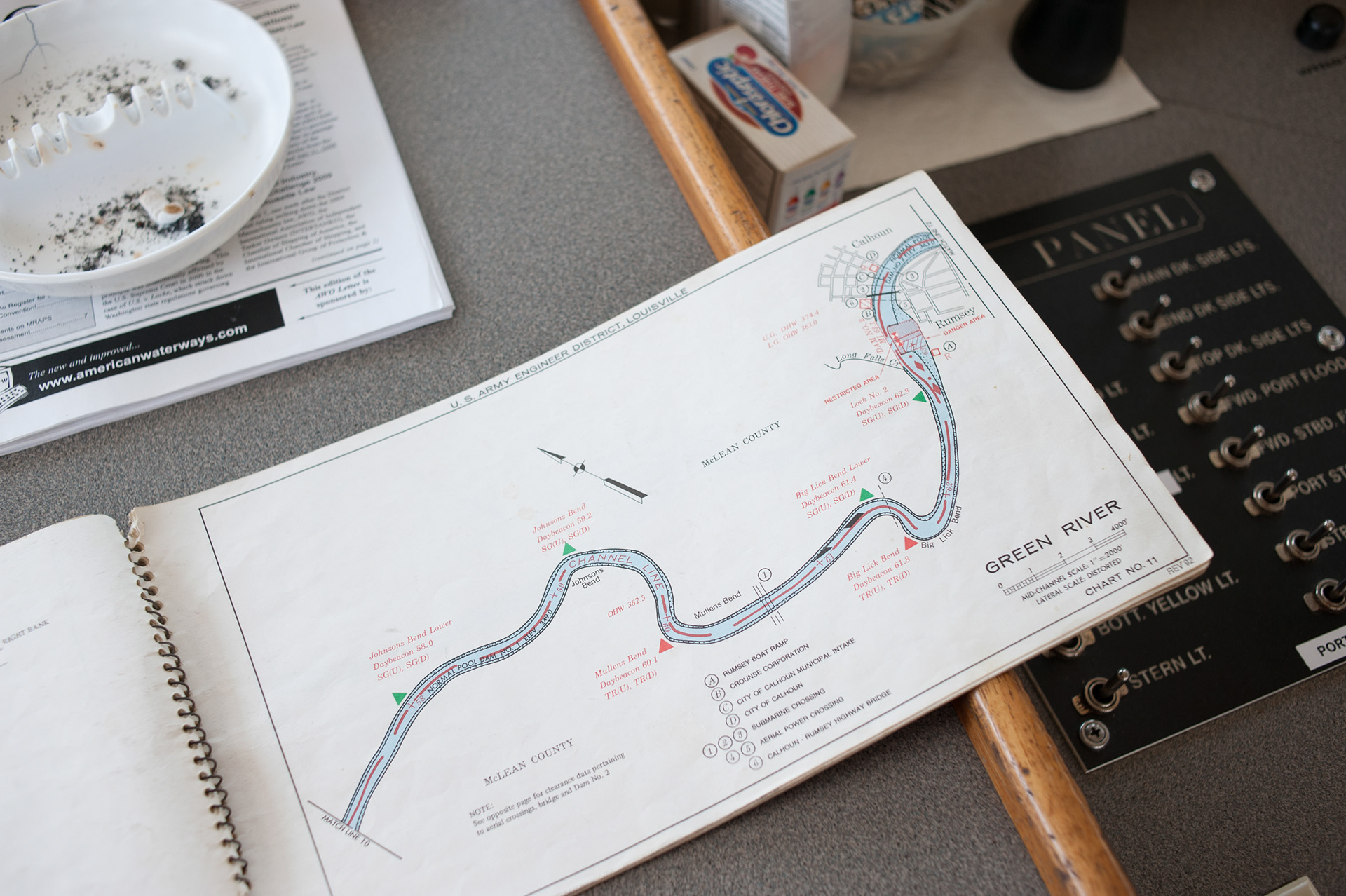

The Green River winds its way through the coal fields of western Kentucky before it empties into the Ohio. Its shipping channel accommodates tows of 2 x 2 barges, each capable of holding 1500 tons of coal. Some of the coal goes only a short distance from the mines to one of the power plants on the Green. The bulk of it proceeds to the river’s mouth, where the barges are rearranged into larger 3 x 5 tows and sent up or down the Ohio. Some Kentucky coal ends its journey in steel mills overseas. Meanwhile, coal from as far away as Wyoming travels in the opposite direction, up the Ohio and up the Green to one of the power plants on its banks. Such are the ways of timed deliveries in a volatile energy market.

Life on a tow has its own rhythm: six hours of work, six hours of rest, two weeks on, one week off. The work is difficult and dangerous. Bad weather adds misery and more danger. The crew budget and shop for food together. They share chores and tight quarters and cook for one another. The farthest retreat is the tow’s bow, four hundred feet away at the end of a narrow path that runs between heaps of crushed coal. Flying dust can make the walk out there very unpleasant.

As if anyone had to be reminded that fossil fuels are messy, the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded the day I was on the river. The garishly colorful TV images in the tug’s common room seemed to come from a different planet. I wish they had.

My sincere thanks for giving me the opportunity and shuttling me back and forth go to Butch Branson and his team, in particular Jim and Jimbo. For sharing their bunk and meals with me and being good sports in front of the lens, I am very grateful to Matt, Wendell, Dan, Jerry, Tron, and Michael.