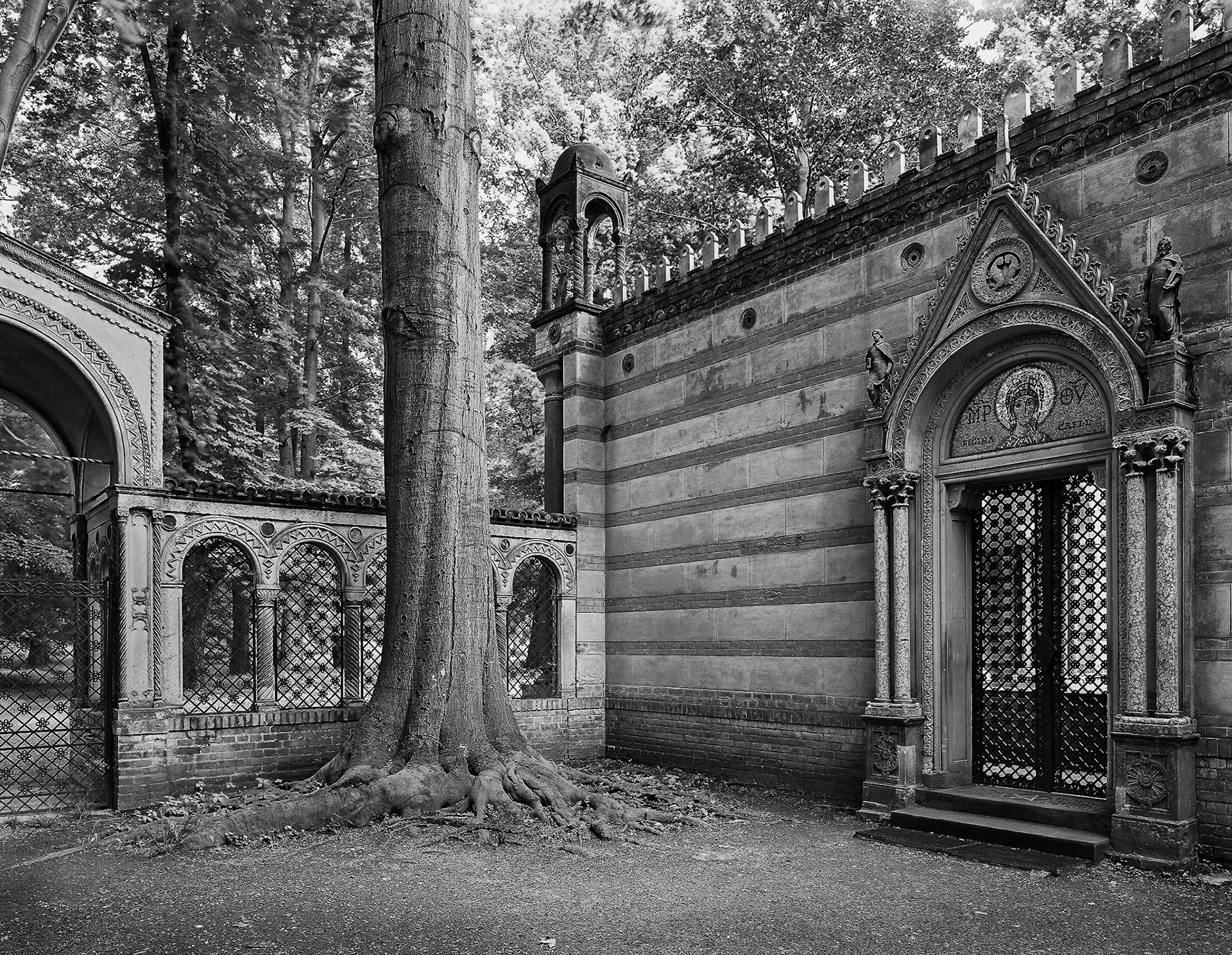

This collection is part of an extended study of Berlin's changing urban landscape about halfway through the frenzied construction process that took off in the mid 1990s. It searches out the less prominent, more idiosyncratic locations that, in my view, are as characteristic of the city as the grander tourist destinations. If a famous monument makes an appearance, then it does so in a hopefully unfamiliar role or an unfamiliar state. Many of the images speak, sometimes obliquely, about history, inertia, and change. They offer glimpses into spaces between one destination and the next.

Remarks about the project are attached below the images.

I first saw Berlin, I believe, in 1974. It was on a high school excursion designed to instill a sense of history in a horde of pubescent teenagers from West Germany by taking us to the place from which the outrage of the second World War and the holocaust had been unleashed. I cannot vouch for my classmates, but it worked on me. The traces of the war and its aftermath were ubiquitous and haunting: ruined buildings, façades pockmarked by shrapnel and bullets, wastelands in the formerly densest parts of the city, overgrown train tracks that no longer led anywhere. And there was, of course, the wall with its wide swath of border fortifications cutting right through what had been the city center. The devastation was much more visible in the East, where post-war cleanup and rebuilding had moved at a much slower pace than in the West. The East was a strange place to visit: drab, gray, and menacing, and expensive to boot: one had to exchange a good chunk of money at an artificially high rate and then had difficulty spending it for want of a consumer culture. Our capitalist privilege made us feel awkward and vulnerable. I cringe when I recall our juvenile stab at boosting, on our journey home, the notoriously short East German supply of tropical fruit by tossing oranges from the train.

My next visit was more involved. I spent the academic year of 1982–1983 as a philosophy student at the Free University, the West’s answer to the renowned Humboldt University that had fallen to the East. West-Berlin was the place to be for anyone in my line of study, and more generally for hipsters, draft dodgers, and creative types of any description. Culture, high, sub, and counter, were vibrant thanks to the quirks and perks of an island city artificially kept alive as a beacon of Western light. Within the confines of the wall, life was more liberal and tolerant and, because of rent control and a squatter movement, less expensive than anywhere in the Federal Republic.

I lived in one of the more leafy districts close to the university, but I distinctly remember the stench of the high sulfur coal that was still burned everywhere for heat and hot water. The winter light had that wonderful soft quality associated with respiratory ailments and a universal blanket of soot. One of my favorite pastimes was to take the S-Bahn (commuter rail) from the neglected Lichterfelde-Ost station in the South all the way up to bucolic Frohnau in the North. The route quickly merged with the former and now defunct main train artery into the city’s once busy Anhalter Bahnhof, then tunneled under the East past Hitler’s bunker, reemerged in the West somewhere north of Bahnhof Friedrichstraße, joined the wall for a while, and then lost itself in the Northern suburbs. There was nothing more exquisitely surreal than sitting in one of the 1930s cars on a wooden bench atop a steam heater and watching the GDR soldiers patrol the shadows on the dimly lit sealed-off platforms beneath the ruins of Anhalter Bahnhof, ready to shoot any would-be escapee attempting to jump on the lumbering train. I can still hear the low hum of the train’s outdated electric motors.

In the summer of 1990, I accompanied my future wife Wallis Miller on her move to Berlin where she was to do archival research for her dissertation in architectural history. The political landscape had changed dramatically with the opening of the wall only a few months earlier. The urban landscape would take its time to catch up. We spent the day of our arrival on a long bicycle ride on the patrol road in the Todesstreifen (death strip) running along the Eastern side of the wall. The wall itself was still largely intact, with the occasional breach for the convenience of Eastern shoppers and Western gawkers as well as graffiti artists in search of new canvases. Redevelopment did not really get underway until a few years later, the time it took to sort out property disputes and organize the logistics for what would be for several years the world’s largest construction site.

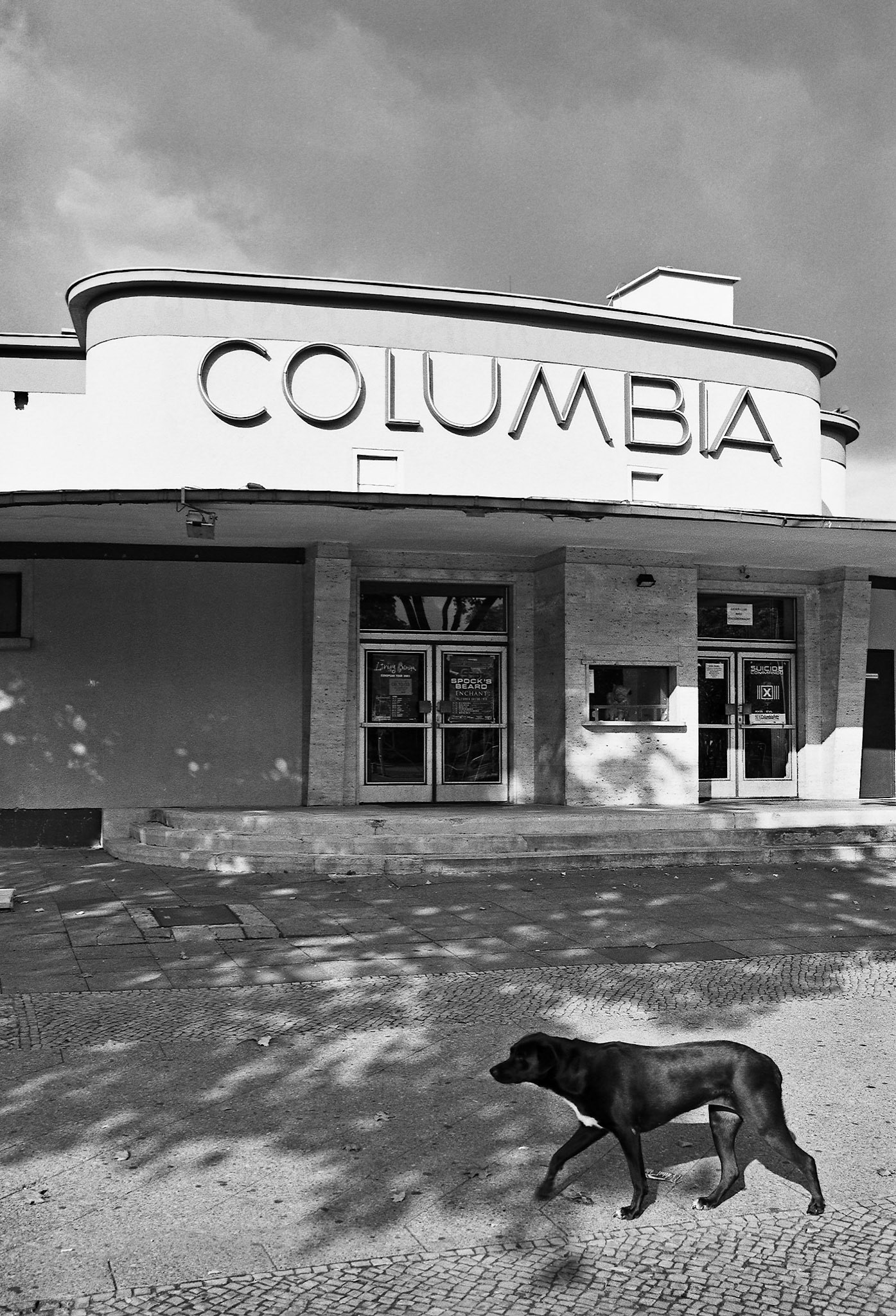

Much of the construction work was drawing to a close when we arrived in 2002 for our most recent extended stay. There were hardly any traces left of the wall’s path. The scrubby rabbit run next to Scharoun's Staatsbibliothek (State Library) and Philharmonie (Philharmonic Hall) had been buried under the Potsdamer Platz shopping and entertainment arcades; the Reichstag to the North, now home to the German parliament, poked out its new glass hat above a new flight of government accommodations; Friedrichstraße had reclaimed its upscale shopping glamour with slapdash entries from a roster of overextended international starchitects. You still found large desolate lots in central places and façades bearing the scars of the street fighting in 1945. But in the foreground, jostling for attention, were scores of new buildings clad in glass, aluminum, and thin sheets of expensive rock. The train system had been refurbished and extended, the stations lavishly rebuilt, housing renovated, crumbling manufacturing sites converted into cultural centers, and the air was much cleaner thanks to the phasing out of coal burning stoves and two stroke engines. These improvements have not made Berlin a beautiful city like, say, Paris, Vienna, or Rome. The city is still unhewn, a hodgepodge of old and new, shabby and elegant, petty and grand, provincial and cosmopolitan, boorish and refined, “white” and multicultural. But she is livelier than I ever knew her, and with the hodgepodge comes an openness and approachability that makes it easy to feel at home there.

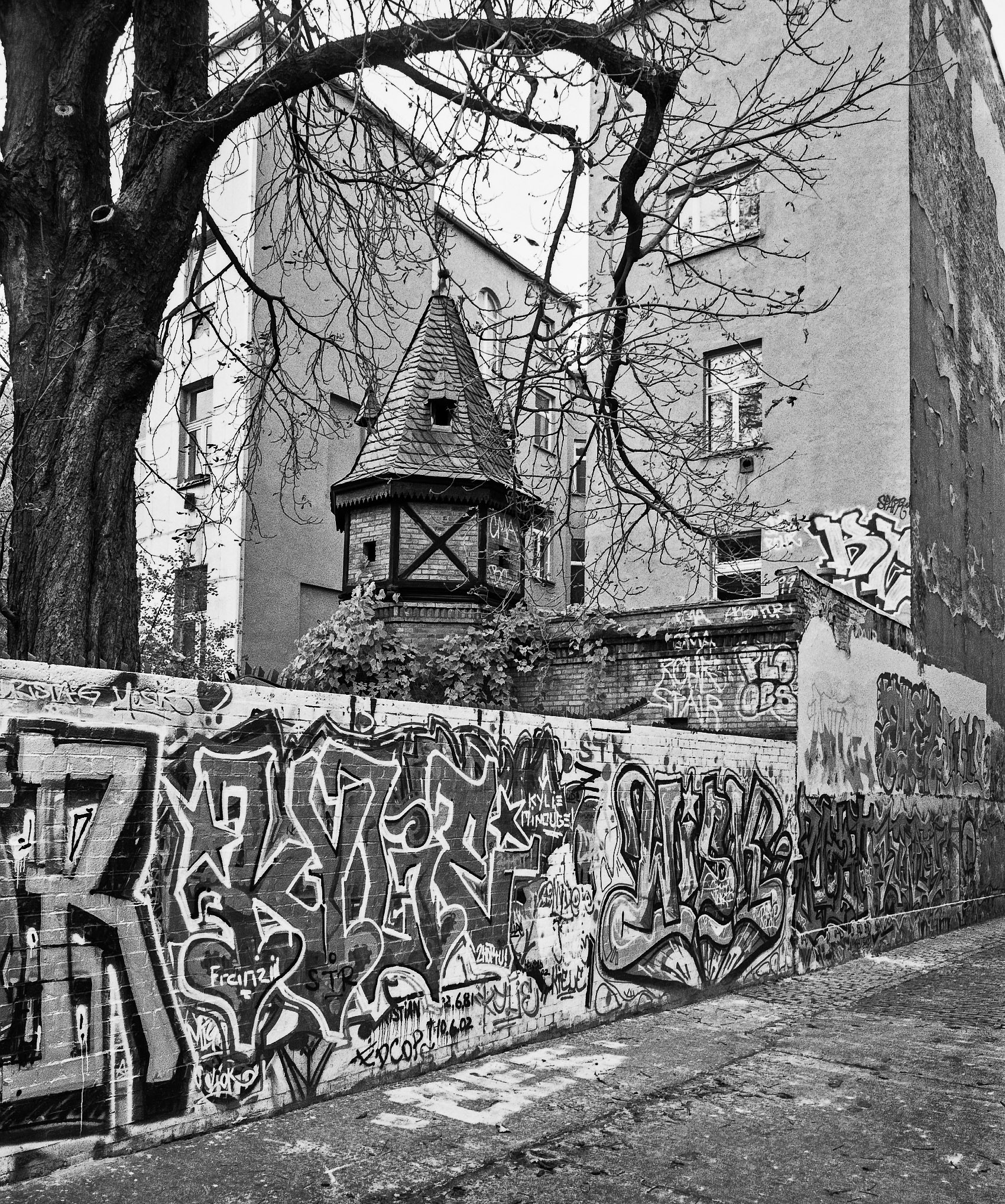

Over a period of 16 months, we had the good luck to experience the city from three very different vantage points: a small, noisy apartment in a Marshall plan building from the 1950s in Turkish Kreuzberg; a serene villa on lake Wannsee whose current occupant (succeeding the American military, a Nazi luminary, and the original banking family) is the American Academy in Berlin that had awarded Wallis a fellowship; and a quiet apartment, also of Marshall plan vintage, in the former Jewish quarter in Schöneberg, a quarter that was, ironically, almost completely destroyed by allied bombs. It was like living in three different cities: Kreuzberg a dense, sometimes uneasy but mostly peaceful ethnic mix in modest six-story Mietskasernen (rental barracks) with Berlin’s best supply of fresh foods and second best graffiti; Wannsee posh, green, aloof, and quiet, among its chief merits the easy access to the royal gardens around Potsdam; Schöneberg a glimpse from the sidelines into the comforts of bourgeois life in spacious 19th century apartments with high ceilings and excellent public transport nearby. The photographic opportunities ranged accordingly.

My view of Berlin, like anybody else’s, is selective and idiosyncratic. It excludes much of the post-1989 glass and aluminum glitz because I find most of it banal and boring. (Besides, this stuff already gets more than its fair share of exposure.) It also excludes the restored splendor of Unter den Linden, which I find neither banal nor boring but very difficult to photograph anew. Instead, my focus is on the less familiar: places that are in, or tell about, transition; on the quieter side streets; on the infrastructure; on forgotten remnants of the past; on juxtapositions of different times; and—again and again—on images: an open category that includes graffiti, posters, and murals, as well as sculpture. On my long walks, these images became silent companions, some of them mischievous accomplices in trespassing, some of them reassuring old friends. They are not just part of the landscape, they inhabit it. Their faces are often its focal points.

I am frequently asked, sometimes reproachingly, why I chose to work in black and white rather than color. There are several reasons for this, some aesthetic, some technical. The decisive technical reason at the beginning of the project was that, in the wet darkroom, the black and white process offers much more control and better print surface and archival quality than any color process. In the digital world, of course, color has had the upper hand from the beginning. But when I started this work in 2002, the look and longevity of digital prints, black and white or color, seemed to me to be no match for conventional prints. Rapid technological advances have meanwhile closed the gap, and my preference for black and white based on technical grounds has all but abated. But aesthetically there is still much to be said for it. Color can be distracting or extraneous, especially in situations where the photographer has little control over the color palette within the frame or over lighting conditions. The abstract tonality of black and white lends coherence where color pictures have a tendency to fall apart. The coherence extends, importantly, to series of pictures taken under quite different lighting conditions and containing objects whose colors refuse to resonate with one another. While I admit that some images in this collection might benefit from color, I think that this is not true for the majority, and that the images work better together in black and white than they would in color (or in a mixture of color and black and white).